By Andrew J Gaetano, PT, DPT, OCS, CSCS

Physical Therapist, Board Certified Orthopedic Clinical Specialist

Capital Area Physical Therapy and Wellness, Malta NY

Everyone has heard of the dreaded “ACL tear” and how an injury to this ligament can quickly put an end to any athlete’s season. Several professional athletes have been known to suffer this injury and we have seen the consequences; anything from missing a season, to ending a career. Though it is widely reported in the media, ACL injuries can certainly still be misrepresented and misunderstood. What exactly is the ACL? Who is most likely to tear an ACL, and why? How can we reduce the risk of doing this? This article will hopefully clear up some of these issues.

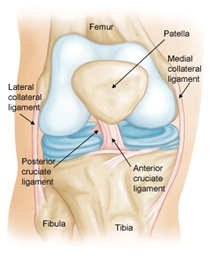

The ACL, or Anterior Cruciate Ligament, is one of the most powerful stabilizing structures in the knee. The main purpose of this ligament is to prevent the lower leg bone (tibia) from moving forward on the upper leg bone (femur). The ACL is paired with another ligament- the PCL or Posterior Cruciate ligament inside the knee joint, both connecting from the tibia to the femur. To picture how these ligaments fit together, cross your right middle finger over your right pointer finger, and put them over your right knee cap. Picture this being inside your knee joint. The middle finger- the one in front, is how the ACL connects the two bones (the pointer finger would be the PCL). In most cases (not all) once an ACL injury or tear has occurred, surgery followed by an extensive rehabilitation program is the best option to correct it and to avoid future injury to the knee.

Figure 1: Front view of a right knee

It’s estimated that 100,000 ACL reconstructive surgeries are performed every year in the United States. Unfortunately, female athletes sustain ACL injuries at a much higher rate than males, and especially in certain sports such as soccer, volleyball, and basketball. About ¾ of ACL injuries are termed “non contact injuries”- which means it was injured during an athletic type of activity such as twisting with your leg with your foot planted on the ground, stopping suddenly while running, jumping and landing on a fully extended knee or with ‘knock knees’, and stretching the knee further than it should. Non contact ACL injuries are the type that hopefully can be reduced though exercise and education. Certain factors, such as strength, skill, conditioning, and poor mechanics may increase risk of injury. There are certain exercises recommended by researchers that may be helpful in reducing the risk of injuring an ACL, especially in female athletes, but also may be helpful for males.

Figure 2: Top: Landing with ‘Knock knees’, poor landing mechanics which may lead to increased risk of ACL injury. Bottom: Landing with proper mechanics, which may decrease risk of ACL injury

Certain exercises which aim to improve strength, control, and timing of leg muscles may be beneficial in reducing ACL injury risk. Below is a list of exercises taken from an American Physical Therapy Association patient education handout (moveforwardpt.com) aimed at doing just that. Be sure to consult with a physician before beginning any exercise program to ensure that you are healthy enough to do so.

These exercises from moveforwardpt.com demonstrate a sample of an injury prevention program and are not intended as a substitute for a treatment program designed by a physical therapist or other health care professional.

1. Single Leg Balance:

Stand on one leg with your knee slightly bent and attempt to maintain your balance for 15 to 30 seconds. Keep your hip, knee, and foot aligned with hip over knee over foot. Do 1-3 sets of 8-12 repetitions on each foot. As this task becomes easy, make it more challenging by increasing the time you stand on your foot and by standing on a soft surface, such as a pillow or foam pad

2. Heel Touches:

Stand on one foot on a solid and sturdy box or a step with the other foot off the edge. With your hands on your hips, bend your stance leg and lower your body down until your opposite heel, on the hanging leg, touches the ground and then push back up. Keep your hips level and your hip, knee and foot aligned while you execute this exercise. Do 2-3 sets of 8-12 repetitions on each foot. If you feel pain in the front of your knee, select a lower step height or discontinue this exercise.

3. Wall Squats:

Lean up against a wall with your back against it and your feet 12-24 inches away from the wall. Bend your knees and slide down the wall until your knees are directly over your ankles. If your knees are positioned over your toes, you have squatted too far. Hold this position for 10 to 30 seconds and push back up to standing. Do 1 set of 5-10 repetitions. To increase the challenge of this exercise, increase the time you hold the squat position and/or add a resistance band around the top of your knees. If you experience pain in the front of your knee, try decreasing the depth of your squat or discontinue this exercise.

4. Single Leg Bridge:

Lay on your back with one knee bent slightly and one leg straight. Using the bent leg as your support leg, elevate your trunk and hips, bringing your shoulders, hips and leg in a straight line. Hold this position for 10-30 seconds. Do 1-3 sets of 10-12 repetitions.

5. Lunge Step:

Stand with your feet together and step forward with one leg, bending your knee to 90 degrees after your foot hits the ground. Make sure the front knee remainsover the ankle and does not go past stepfoot. Continue moving your body forward by bringing your back (stationary) leg forward, then together with your step leg. Alternate legs with each step. Do 2-3 sets of 10-15 repetitions.

6. Broad Jump:

Stand with your feet shoulder width apart and jump forward, landing on both feet.

Focus on taking small, controlled jumps and landing with equal weight distribution on each leg. Concentrate on soft, quiet landings and maintaining your lower extremities in good alignment, with your hips over your knees, and knees over your feet. Make sure your knees do not come together when you land from this jump. Over time, this exercise can be progressed by increasing the length of the jump. This exercise should be monitored either by a partner or with a mirror.

If you are concerned about ACL injury and want to find more ways on how to reduce your risk, be sure to contact Capital Area Physical Therapy at 518-289-5242, and we will be able to develop an individualized program based on an examination.

https://capitalareapt.com Malta NY